This story is the last in a series on stock market crashes. Part I is here, Part II is here Part III is here.

You may think that the pandemic did enormous damage to the US (and world) economy, but the NASDAQ index says otherwise.

Shutdowns of service industries for months because of lockdowns? Nothing to worry about.

Disruptions in the supply chain? ‘Tis but a scratch.

Rampant inflation and consumer good shortages? Really, man, you should chill and cut out the bad vibes.

The black knight in Monty Python’s Holy Grail has nothing on the Nasdaq index over the last three years.

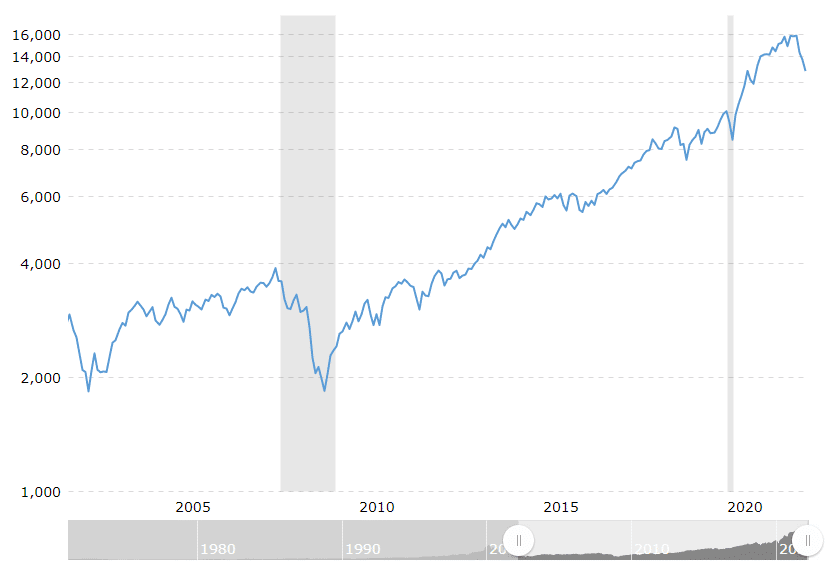

Even with the recent correction, the NASDAQ is trading above 13,000 points. At the nadir of the 2008 crash, it was below 1700.

In 13 years, the NASDAQ has given investors a 17% return (compounded annually), in an era of little or no inflation.

For many tech investors, good times are all they have known, except for the brief blip in 2020.

But in the first decade of the 21st story, investing in tech was a completely different story. After the savage bear-market of 2000-2002, the NASDAQ managed to double to 4000 by 2007, although it was still more than 20% off its all-time high of 5000 in 1999.

But then it crashed back to its 2002 lows. If you were a tech investor in the 2000s, you made no money for a decade.

To add insult to injury, the cause of the crash had nothing to do with tech, but with the collapse of the US housing market due to Wall Street shenanigans over junky bonds and mortgage debt.

(A most enjoyable way to learn about the cause of the 2008 crash is to watch the movie “The Big Short” or read the book of the same name.)

Could the market crash today for the same reason that it crashed in 2008?

I don’t think so.

In 2008, when the markets realized that much of the paper in the market was garbage, the dump started, continued for months and inevitably the market ran out of bag-holders.

And institutions started going bankrupt, as the market finally figured out the paper they held was worth nothing.

But then the Fed stepped in, started buying everything in sight, and bailed out the market.

Financial conservatives were shocked, thinking this was going to lead to rampant inflation and “moral hazard,” a concept that today’s investors would do very well to learn about.

But it didn’t. The bailouts worked very, very, well (at least in covering the collective rear-end of the Wall Street and the banks. The average homeowner, not so much). Inflation stayed dormant.

Then COVID hit in 2020, the markets tanked, and the US Fed said, “Hold my beer.”

By this time, the disciples of Modern Monetary Theory had been anointed the new high priests of finance and the followers of Milton Friedman banished to the shadowlands (if you have never heard of Friedman, don’t worry about it, he’s just some dead white guy).

And here we are. The past events of the last few years could not have been predicted, but only if you looked at the last 20 years. Zoom out 50 or 100 years, and present-day turmoil was inevitable.

Bad stuff happens. When we have a blessed period in history with no black swans, like 1990-2000 or 2010-2019, markets bloom and the average Joe can frolic in the sun.

It’s easy to second-guess the central bankers but there was a method (or reason) to their madness.

Deflation was the greatest fear of the central bankers for the first 20 years of this century (and they had a point – Japan had a deflationary stagnant economy since the 1990s).

But that’s not a problem for the US or the rest of the world anymore.

And this is where it gets interesting.

Suppose the market doesn’t crash, but inflation runs at 7% for the next three years?

Compounded annually, that’s a loss in purchasing power of nearly 23%.

Hyper-inflation means the market doesn’t have to go down (very much) to do a reset.

An investor’s portfolio is worth less year-over-year, but the financial adviser doesn’t have to explain why except to roll his or her eyes and blame whoever is holding public office at the time.

As an added bonus, remember all that US debt bought up by foreigners? No need to default, just pay back with cheaper dollars.

It’s a win all around. Well, except for the average retail investor. And pension funds. But let’s not talk about that.

Brave New World

So where do we put our money? Bitcoin, some other crypto asset, gold, silver, dividend stocks, nickel, real estate, or six-packs of Coca-Cola?

At some point in the cycle (which is going to last for years, by the way), it’s yes to all of them, at different times.

In the month of March, we have looked at four different periods in history where the stock market crashed. All four crashes were different, but one thing was in common in all of them.

Crashes are a reset.

What worked before for easy riches, doesn’t work anymore. Something new takes its place.

And the new new thing will at first be met with indifference, then surprise, and then hostility by the establishment.

Finally, it will be loved and emulated. But only after great fortunes have been made by contrarian investors who got in early.

DJ